While the U.S. public transportation industry has long had a significant bus operator shortage, it has been magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has not only exacerbated existing trends, but also introduced new labor market dynamics. This brief describes overall workforce trends for bus operators, obstacles to recruitment, and challenges for workforce retention, to help inform efforts to recruit more drivers nationwide.

Overall workforce trends

According to 2020 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data, there are 162,850 bus operators nationally. Federal government projections indicate strong growth for bus operators; BLS estimates the occupation will grow “much faster than average (15 percent or higher).”[1] To keep up with growth and make up for retirements and turnover, the industry will need to recruit scores of new workers. BLS reported an annual average of 24,600 projected bus operator job openings for 2020 to 2030.[2]

According to BLS, annual wages for the occupation were $45,900 in 2020, which was higher than the national median of $41,950.[3] Despite having a reputation for paying relatively well and providing robust benefits,[4], [5] transit agencies have faced significant challenges to recruit workers in sufficient numbers to meet the growing demand. The rise of COVID and the omicron variant have created a “labor crisis” in transit, leading Houston Metro to offer bonuses of $4,000 for new drivers, and NYC to try to lure workers out of retirement, for example.[6]

Demographic challenges

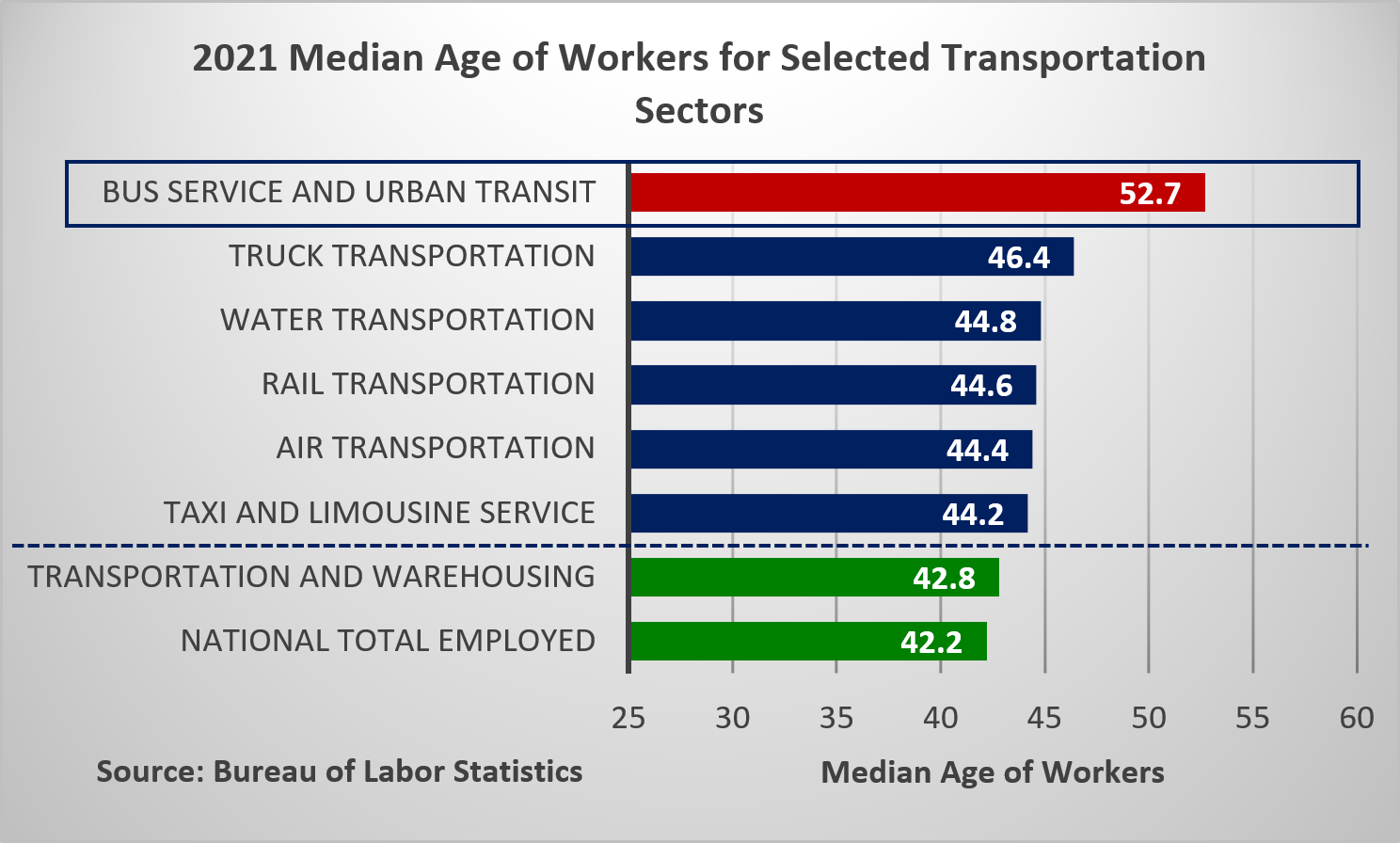

One major demographic challenge contributing to the current operator shortage is the disproportionately older bus operator workforce. As Figure 1 on the next page shows, the median age of U.S. workers was 42.2 years in 2021, and 42.8 years in transportation and warehousing. For the bus service and urban transit industry, it was 52.7, which is substantially higher than both the nationwide median age for workers and the median age for other subsectors within transportation and warehousing, such as air or rail transportation.[7] The higher median age of urban transit workers is largely attributable to the older age of bus drivers (median 53.3 years)[8], who constitute 60 percent of the workforce[9]. A large percentage of workers are expected to retire in the coming years.[10], [11]

COVID-related health and safety issues

Figure 1. 2021 Median Age of Workers for Selected Transportation Sectors

As frontline workers, bus operators risk exposure to COVID-19, and serious health consequences, even death. For example, in New York City, 136 MTA operators died around the start of the pandemic.[12] As of December 2021, more than 2,000 COVID cases have been reported among WMATA workers since the pandemic began; seven of the workers died. According to CTAA, some member agencies have experienced as many as 40 percent of their operators absent from work due to sickness.[13] COVID-related factors have resulted in bus operator shortages and service cuts,[14] a trend which has occurred in transit systems nationwide. In addition, some drivers have quit due to fears about the virus or been terminated due to failure to comply with vaccination and testing policies.[15]

Pre-existing labor market dynamics

The pandemic has also exacerbated existing workforce challenges, such as competition for pay. Stakeholders interviewed for a GAO study reported that other industries which hire workers with similar levels of education, including fast food, may attract workers instead of transit, especially in rural areas or areas with low unemployment.[16] When the economy is strong, construction also tends to attract workers who might otherwise work in transit. Furthermore, some workers leave the transit industry once they have earned their CDL.[17]

CDL and new requirements

Transit bus drivers are generally required to hold Class B Commercial Drivers’ Licenses and passenger (P) endorsements. Due to the high cost of self-funding CDL training, employer-sponsored training programs in which costs are covered, such as those run by transit agencies, are an attractive option for job seekers. However, the potential exists for trainees to pursue employment in commercial driving or another sector after completing a transit-oriented training program.[18] This dynamic is particularly challenging given concurrent shortages of truck and school bus drivers.[19]

Individuals are required to hold a standard driver’s license to qualify for a commercial learners’ permit, which in turn is needed to pursue CDL training.[20] These requirements may impact recruitment of young people, as rates of driver’s license attainment for 18–24 year-olds have decreased slightly in recent decades and may be lower during recessionary periods and among residents of cities.[21]

Regulatory changes impacting entry level driver training (ELDT) may also affect agencies’ ability to fill positions. As of February 7, 2022, the FMCSA has started enforcing universal training standards for entry level driver training and maintaining a database of qualified providers (the Training Provider Registry).[22] Professional organizations representing transit agencies such as APTA and CTAA have expressed concern about these additional regulatory requirements. Agency contacts have also identified challenges related to requirements around license renewal, medical fitness testing, the availability of training during the pandemic and delays with local DMVs processing CDL application due to pandemic staff shortages. FMCSA has granted waivers around certain other CDL requirements during the pandemic, and recently announced a grant to support state capacity for CDL licensing, though the emphasis appears to be on commercial trucking. [23], [24]

Assaults against drivers

Driver safety has been a persistent problem. Assaults against drivers and altercations with passengers have been well-publicized in communities that transit serves.[25], [26]A 2015 Monthly Labor Review article identified violence as a key challenge facing drivers, with examples including a 2012 attack with rocks in Washington, DC and a 2013 shooting in Seattle.[27] More recently, drivers have reported increased stress during the pandemic and face threats including violence related to passenger non-compliance with mask mandates, among other issues. Such incidents have deterred potential applicants from considering a transit driving career and contributed to early retirements.[28]

Lack of interest from younger generations

Younger workers have different expectations about the workplace, which has made it challenging for agencies to recruit them. Younger workers tend to value flexible schedules, yet operators must often work on holidays and weekends, especially when they first start in the field. New hires in general may not find this attractive.[29]

Advances in technology

Advances in technology present challenges to recruitment and retention. The rise of automation and apps requires drivers to possess technical knowledge to operate newer buses and assist customers; this means there is a relatively small pool of qualified workers. Additional and new types of training are needed for both incumbent and new workers to adapt. Furthermore, drivers report feeling stress from being monitored more often by cameras and tracking technology.[30], [31]

Stress and burn-out

Finally, being a bus operator is a highly stressful occupation. Drivers must operate large vehicles on congested city streets on tight time schedules.[32] They work relatively long hours with infrequent breaks.[33] As discussed earlier, technological advances have contributed to worker stress as well. Operators also experience burn-out due to the stress of dealing with passengers, who may ignore COVID safety rules,[34] or be unruly or violent.

Conclusion

Bus operators have been in short supply for years, and this problem has been magnified by COVID-19. An aging workforce and labor exits related to COVID have largely contributed to the shortage. Top obstacles to recruitment and retention include pandemic-related health and safety issues, pre-existing labor market dynamics including competition over pay, CDL requirements, assaults against drivers, and lack of interest from younger generations. Other contributing factors include advances in technology, perceptions of inflexibility, and stress. To address these workforce recruitment and retention issues for bus operators, key stakeholders from management and labor should keep these data and trends in mind.

Bus Operator Recruitment Campaign

The Transit Workforce Center (TWC) is currently developing a national campaign in coordination with the FTA, along with key labor and industry partners, to effectively address the national bus operator shortage. The TWC is preparing to create a toolkit of materials designed to be adapted by agencies and labor union locals that will consist of templates for commercial scripts, postcard mailers, exhibit banners, talking points for public meetings, social media postings, informational video scripts, and letters of introduction. If any organization has existing models that should be incorporated into these plans, please contact Senior Communications Specialist David Stephen at dstephen@transportcenter.org.

Contributing Authors: Benjamin Kreider (Consultant); Xinge Wang; Douglas Nevins

[1] Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2020. 53-3052 Bus Drivers, Transit and Intercity. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes533052.htm

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table 1.7: Occupational projections, 2020–30, and worker characteristics, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/occupational-projections-and-characteristics.htm.

[3] Summary Report for: 53-3052.00 – Bus Drivers, Transit and Intercity. O*Net Online. https://www.onetonline.org/link/summary/53-3052.00?redir=53-3021.00.

[4] Shared-Use Mobility Center. “Case Study: Managing the Labor Shortage at Transit Agencies.” November 5, 2021. https://learn.sharedusemobilitycenter.org/casestudy/managing-the-labor-shortage-at-transit-agencies/.

[5] Laura Bliss. “There’s a Bus Driver Shortage. And No Wonder.” Bloomberg City Lab. June 28, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-06-28/there-s-a-bus-driver-shortage-and-no-wonder.

[6] Eli Rosenberg. “Labor shortages are hampering public transportation systems, challenging the recovery of city life.” Washington Post. December 28, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/12/28/worker-shortages-public-transportation/.

[7]Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table18b: Employed persons by detailed industry and age. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18b.htm.

[8] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table 11b: Employed persons by detailed occupation and age, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11b.htm.

[9] Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Employment Matrix. https://data.bls.gov/projections/nationalMatrix?queryParams=485100&ioType=i.

[10] Jack Clark. Testimony before the House Transportation Infrastructure Subcommittee on Highways. March 13, 2019. https://transportation.house.gov/imo/media/doc/Testimony-%20Clark.pdf.

[11] Robert Puentes et al. “Practitioner’s Guide to Bus Operator Workforce Management.” Transportation Research Board of The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. November, 2021. Unpublished interim report.

[12] Benito Perez. “After COVID, who’s driving the bus?” Transportation For America. Nov 2, 2021. https://t4america.org/2021/11/02/bus-operator-shortage/.

[13] Justin George. “Omicron deepens bus driver shortage, frustrating passengers as transit agencies pare back service.” Washington Post. January 15, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/01/15/covid-omicron-bus-transit/

[14] Justin George. “Bus operator shortage due to covid prompts Metro to reduce bus service.” Washington Post. December 23, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2021/12/23/dc-metro-bus-shortage-covid/.

[15] “MARTA Making Temporary Service Modifications to Address Bus Operator Shortage.” Metro Magazine. https://www.metro-magazine.com/10155945/marta-making-temporary-service-modifications-to-address-bus-operator-shortage. November 12, 2021.

[16] US Government Accountability Office. “Transit Workforce Development – Improved Strategic Planning Practices Could Enhance FTA Efforts.” GAO-19-2090. March 2019. https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/697562.pdf. P. 15.

[17] Puentes et al., 2021.

[18] Puentes et al., 2021. P. 37.

[19] Bliss, 2021.

[20] FMCSA. “Commercial Driver’s License: States.” December, 2019. https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/registration/commercial-drivers-license/states

[21] Tefft, B. C. & Foss, R. D. “Prevalence and Timing of Driver Licensing Among Young Adults, United States, 2019.” October, 2019. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. https://aaafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/19-0500_AAAFTS_Teen-Driver-Safety-Week-Brief_r1.pdf

[22] FMCSA. “Commercial Driver’s License: Entry-Level Driver Training (ELDT). February, 2022. https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/registration/commercial-drivers-license/entry-level-driver-training-eldt

[23] FMCSA. “Waiver in Response to the COVID-19 National Emergency –For States, CDL Holders, CLP Holders, and Interstate Drivers.” December 15, 2020. https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/emergency/waiver-response-covid-19-national-emergency-states-cdl-holders-clp-holders-and-1

[24] U.S. DOT. “DOT, DOL Announce Expansion of Trucking Apprenticeships, New Truck Driver Boards and Studies to Improve the Working Conditions of Truck Drivers.” January 13, 2022. https://www.transportation.gov/briefing-room/dot-dol-announce-expansion-trucking-apprenticeships-new-truck-driver-boards-and

[25] Puentes et al., 2021. P. 36.

[26] Luz Lazo. “Citing attacks directed at buses, Metro weighs service cuts in Anacostia.” Washington Post.

[27] Bureau of Labor Statistics. “When the wheels on the bus stop going round and round: occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities in public transportation.” 2015. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/when-the-wheels-on-the-bus-stop-going-round-and-round.htm#_edn1..

[28] Chris Teale. “Transit workers face growing rate of assaults: ‘There’s not much we can do.’” Smart Cities Dive. February 17, 2021. https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/transit-workers-face-growing-rate-of-assaults-theres-not-much-we-can-do/594959/

[29] Puentes et al., 2021.

[30] Puentes et al., 2021.

[31] GAO, p. 16.

[32] Bliss, 2018.

[33] GAO, 2019; Puentes et al., p. 14.

[34] Justin George. “Omicron deepens bus driver shortage, frustrating passengers as transit agencies pare back service.” Washington Post. January 15, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/01/15/covid-omicron-bus-transit/.

Related Topics:

Hiring and Recruitment, Retention, Safety and Health, Workforce Shortage